#Trànsits 2024-2025 (recap of the spring sessions: Legong, Caramelles del Roser and Sounds of Buddhism)

Spring 2025 saw more sessions in the ‘Trànsits: les músiques de l’esperit’ [Transitions: Music of the Spirit] programme, organised for the third year running by the Museu de la Música de Barcelona and the Religious Affairs Office (OAR) as part of the ‘(Contra) Natura’ season at L’Auditori. In March, April and May, the following sessions were held: ‘Legong, Music and Dance of the Balinese Gamelan’, ‘Les Caramelles del Roser: “Goigs” and Easter songs’ and ‘Sounds of Buddhism: The Dharma sound experience’, this last one closing this year's edition.

Sound is used in many religious and spiritual traditions to stimulate reflection and inspire transcendence. This multiplicity of uses makes music a common feature of many beliefs, convictions and cultures. For three editions, the series ‘Trànsits: les músiques de l’esperit’ [Transitions: Music of the Spirit] programme, organised by the Museu de la Música de Barcelona and the Religious Affairs Office (OAR), has been exploring this essential relationship this year as part of the ‘(Contra) Natura’ season at L’Auditori. Jordi Alomar, director of the Museu de la Música, spoke to us in an interview: ‘Taking the religious and spiritual dimension as a starting point is a highly effective way to work on interculturality, because spirituality is an essential component of human groups’.

In the spring of 2025, three sessions were held as part of this series: ‘Legong, Music and Dance of the Balinese Gamelan’, ‘Les Caramelles del Roser: “Goigs” and Easter songs’ and ‘Sounds of Buddhism: The Dharma sound experience’.

LEGONG. MUSIC AND DANCE OF THE BALINESE GAMELAN

The activity Legong, Music and Dance of the Balinese Gamelan’ was held on 5 April, where the audience was able to enjoy a display of legong, a traditional dance from the island of Bali that is accompanied by a gamelan, a set of traditional percussion instruments from the Indonesian islands of Java and Bali. Prior to the display, a conversation was held between Anak Agung Bagus Harjunanthara ‘Arjuna’, a dancer, choreographer and director of the Arjuna Production Art Community on Bali; Eka Santi Dewi, a dancer and educator; and Nyoman Hardiani Dewi, a cultural role model from the group Gamelan Barasvara, who are currently residents at the Museu de la Música de Barcelona.

The conversation revolved around the scope of gamelan and its identity significance for Balinese people in the diaspora. This phenomenon is associated with religious ceremonies and celebrations on Bali, but gamelan can also be performed in many other settings. Hardiani Dewi’s opinion, finding the Gamelan Barasava in Barcelona meant discovering a little bit of his land in the city. Arjuna, in turn, said: ‘It is appreciated and respected in Europe. I detect passion in every rehearsal, which makes me love my culture even more.’ Still, the nature of gamelan as a ‘space for gathering’, according to Hardiani Dewi, means that it is a practice that can be shared anywhere.

There are different types of gamelan, and even though they vary by setting they are not exclusively linked to them. Gamelan Beleganjur was mentioned in the conversation, which is often played in processions, as well as Gamelan Anklung, which is primarily performed in religious cremation ceremonies. The concert held after the conversation featured a display of Gamelan Gong Kebyar, in which bronze instruments are played with sudden contrasts in tempo and texture. It is the most popular kind on Bali, has existed for a century and is usually accompanied by dances (kebyar duduk). They can be feminine-refined(halus), male-strong (keras) or androgynous (bebancihan), and they can be performed by people of any gender, given that they are only characters. At the Gamelan Barasvara display at the Museu de la Música, these dances were performed by Arjuna and Eka Santi Dewi. Still, the concert exemplified the important role of Balinese Gamelan as a space of social gathering, collective ownership and interaction.

See the picture gallery of the conversation on ‘Legong: Music and dance of the Balinese Gamelan’ HERE and of the Legong display HERE. The videos of both sessions will soon be posted on the OAR blog.

LES CARAMELLES DEL ROSER: ‘GOIGS’ AND EASTER SONGS

The activity ‘Les Caramelles del Roser: “Goigs” and Easter songs’ was held on 10 May. It featured the Association of Caramelles del Roser of Sant Julià de Vilatorta, a historical ensemble that still upholds the tradition of walking through the streets singing while wearing their own costumes to accompany their characteristic singing of the ‘goigs del Roser’ and local compositions. As usual at Trànsits, the activity began with a conversation on this practice. The participants included Ignasi Roviró Alemany, member of the Folklore Research Group of Osona, and Hernan Collado Urieta and Sebastià Bardolet, president and deputy director, respectively, of the Association of Caramelles del Roser of Sant Julià de Vilatorta.

The Caramelles del Roser are the oldest ones documented in Catalonia. They are associated with Easter, but they are also ‘songs to celebrate the springtime, that time when the earth comes back to life,’ said Collado. These songs are closely related to religious and civil life not only because they mix religious ‘goigs’ and springtime ‘caramelles’ but also because they are performed in a procession through villages and cities, transforming them as they go. ‘The sounds of the street’, Roviró said, ‘hush when the procession goes by, and during it the music creates a new space, which goes back to normal after the singing ends’. These songs came to Sant Julià de Vilatorta with the creation of the Confraria del Roser [Brotherhood of the Rosary] in 1590, dedicated to devotion to Our Lady of the Rosary, and they became an emblem of the village. The town has a very important musical tradition, and the Association, which was founded fifty years ago to keep this practice alive, has an exclusive repertoire of 50 pieces created by the residents themselves.

After the conversation, the Association of Caramelles del Roser of Sant Julià de Vilatorta offered a singing procession through the streets of Ciutat Vella district. The audience was able to experience the traditional format of the Caramelles del Roser: around 35 singers wearing black with a top hat and staff, arranged in two rows (first voices and second voices, the basses at the end) repetitively singing the ‘goigs del Roser’. A string band started the verses, which were repeated up to eleven times. After that, they made stops to sing a ‘caramella’ or a song composed by a resident of Sant Julià de Vilatorta at each one. Thus, the recital showed how this tradition ‘has made a symbiosis between “goigs” and “caramelles”, between religious and civil’, said Bardolet. After the procession, following tradition, the route finished with a Celebration of the Word at Sant Pere de les Puel·les parish church

See the picture gallery of the conversation on ‘Les Caramelles del Roser: “Goigs” and Easter songs’ HERE and of the route and the Celebration of the Word HERE. The videos of both sessions will soon be posted on the OAR blog.

SOUNDS OF BUDDHISM: THE DHARMA SOUND EXPERIENCE

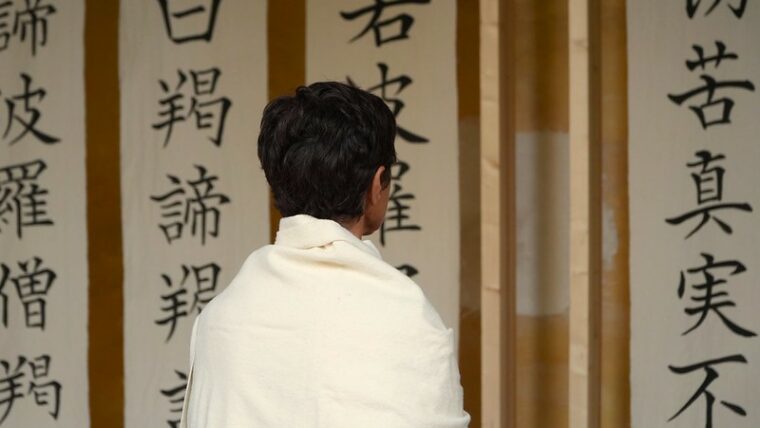

This edition of ‘Trànsits’ closed with ‘Sounds of Buddhism: The Dharma sound experience’, a special session that lasted over three days devoted to putting into practice and reflecting on the role of sound and music in Buddhism. From 22 to 24 May, the Reial Monestir de Santa Maria de Pedralbes offered different conversations, workshops, meditations and concerts. Teaming up for this final session were the Reial Monestir de Santa Maria de Pedralbes, Casa Àsia and the Catalan Coordinator of Buddhist Entities (CCEB).

Of all the activities held over the course of the three days, three particularly stand out. The first is the conversation on ‘Sound, music and senses in Buddhism’, in which lama Ngawang Norbu from Casa Virupa; Elisabeth Serrano Ferré from Soka Gakkai and Ngagmo Ngawang Dëter from Sangha Activa talked about the sound dimension in the rituals, meditations and daily life of their respective Buddhist traditions. Vajrayana Buddhism, Ngagmo Ngawang Dëter said, values silence in meditation but leaves lots of spaces where musical instruments play a crucial role, which ‘at first seem like little more than sound, but actually have internal, coded logics’. In Nichiren Buddhism, vocal sound prevails and ‘helps to connect with a personal vibration’, Serrano explained. All three speakers also highlighted music as a point of ‘openness and gathering with the community’, Norbu said. Yet they all stressed using music to facilitate intentional attention concentrated on transcendence, which entails not denying the aesthetic enjoyment of music but allowing it to accompany the individual on this journey. ‘We don’t see it as nullifying desire’, Norbu continued, ‘but as educating it. And music can be one way to do this, to inspire and connect with things.’

The three days also featured two concerts. The first was a concert of the shakuhachi, a bamboo flute used by Japanese komusō Zen monks when practising suizen or ‘blown meditation’, during which its own repertoire was played, the honkyoku. Kakizakai Kaoru, an internationally renowned master of this instrument, featured in this recital. A concert of the Satsuma-biwa was also held, a traditional Japanese lute associated with the epic stories of feudal Japan whose traditional repertoire includes core values of Buddhism like the transitory, impermanent nature of things. This concert featured the master Junko Ueda.

See the picture gallery of the conversation-colloquium ‘Sound, music and senses in Buddhism’, of the concert featuring the honkyoku repertoire and of the concert featuring the Satsuma-biwa HERE. The videos of all three sessions will soon be posted on the OAR blog.